The San Diego Yacht Club was the site of our October 20, 2012 meeting. Our program on Stephen Hopkins – After Jamestown and on to Plimouth drew 43 members and guests to hear Kenneth Whittemore, Jr., and Bev Nickerson, two Hopkins descendants, profile their ancestor.

Governor Ginny Gotlieb opened the meeting and received approval of the minutes of our annual meeting on June 30. Those members in attendance received a copy of our new 2102-13 Yearbook, produced by Secretary Julie Plemmons. The attendees introduced themselves.

Governor Gotlieb repeated the need for financial support for the repair and restoration of the 17th century church bell tower (see the Jamestown Archaeology page on our web site.) She reiterated that the Society has established a special fund to which First California Company has donated $500, complemented by several members. Please make your donations payable to The Jamestowne Society (note your check memo as “Bell Tower Restoration Fund”) and send them to Harry Holgate, Treasurer, First California Company, 115 West Fourth Street #208, Long Beach, CA 90802.

Our next meeting will be held on Saturday, January 19, 2013 at the Mission Inn, 3649 Mission Avenue, Riverside CA 92501. The program will be announced soon, members will be notified and details posted on our blog.

Governor Gotlieb also reminded the meeting of the recent publication of Martha W. McCartney’s Jamestown People to 1800, which is available from Genealogical Publishing Company and on Amazon (see our September 3rd post.).

Chaplain Martha Pace Gresham offered a reflection and blessing for the meal.

After lunch, Lieutenant Governor Donna Derrick introduced our two speakers (see below) who presented their program on the life and family of Stephen Hopkins after he departed Jamestown. Following is a summary of their remarks.

Stephen Hopkins – After Jamestown and on to Plimouth

Stephen Hopkins is best known to Jamestowne Society members as one of the Sea Venture castaways. A shopkeeper in Hampshire, southwest of London, he left his wife and three children for Virginia in 1609, and was famously shipwrecked on Bermuda among those who then came to Jamestown in spring 1610.

He had returned to England by 1617 as a widower. He then remarried and again came to America on the Mayflower in 1620 with his wife and three children (a daughter was born on the trip).

“Pilgrims” was a collective term for the entire group of Mayflower voyagers. He was not a member of the group who were famously seeking religious independence from the Anglican Church (the “Separatists,”) but one of the “Strangers” that the expedition’s financial backers also sent to help assure the success of the new English settlement.

To finance their settlement, the Pilgrims formed a joint-stock company with some 70 English Merchant Adventurers, who obtained a patent for the settlement from the Virginia Company of London, which had also underwritten the founding of Jamestown.

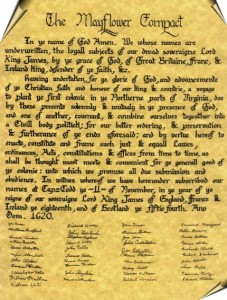

After leaving England in September 1620 and 66 days at sea, the Mayflower made landfall on Cape Cod in early November, but not the destination site of the backers’ patent (in “Northern Virginia” near the mouth of the Hudson River). The Pilgrims’ initial days on landing were extremely trying, and they entered into the  Mayflower Compact to cement a mutual political agreement for their governance (which remained in place until 1691); Hopkins was among the signers.

Mayflower Compact to cement a mutual political agreement for their governance (which remained in place until 1691); Hopkins was among the signers.

He was a fairly active member of the Pilgrims shortly after arrival, perhaps a result of his being one of the few individuals who previously had been to Virginia.

In March 1621, the first local Indian to welcome them, Samoset, walked into Plymouth and stayed in Hopkins’ house for the night. Hopkins was also sent on several of the ambassadorial missions to meet with the various Indian groups in the region.

The winter of 1620-1621 brought disease and death to many “unseasoned” Plymouth settlers. Almost every household lost a husband, wife or both; almost half the colonists perished. Stephen and Elizabeth Hopkins’ family were one of only three households that did not lose a parent, but among their dead was their baby, Oceanus. At the colony’s lowest ebb, only seven people were healthy enough to tend the sick.

The Mayflower returned to England in April 1621, and the Merchant Adventurers obtained a new, more appropriate patent from King James I, confirming the Pilgrims’ settlement and governance of Plymouth. They were allotted 100 acres for each settler that they had transported.

By 1623, productivity and morale were low after the first few years under the system of communal land ownership and cultivation. The colonists suffered hard times from a drought. They also resorted to fishing or clam digging for subsistence. A few were appointed to hunt deer to be divided among the members of the community.

In March, Governor William Bradford and his advisors decided a change was needed. The land would still be collectively owned, but the leaders assigned one acre to each colonist for their personal subsistence. Under this “1623 Division of Land,” the Hopkins family received six acres of land to cultivate for the six members of the family at that time.

In 1624, John Smith related that Plymouth’s population was about 180 persons and that 32 houses had been built.

1627-1651 is the oldest record book of the Plymouth settlement and begins with the 1623 Division of Land, recorded in the handwriting of Governor William Bradford, which included what was assigned to Hopkins.

While the new land arrangement achieved subsistence level living, the colony was producing few profits. The colony’s chief crop, Indian corn, was traded with Native Americans to the north for highly valued beaver skins that were sold in England to help pay the colony’s debts and buy necessary supplies. However, pirates intercepted and looted two ships loaded with trade goods that were to provide the first payments of its debt. The Merchant Adventurers were becoming increasingly impatient.

Most of the Pilgrims held some stock in the joint-stock company, which negotiated a more favorable contract in 1626. In 1627, five London merchants and 53 Plymouth freemen, including Hopkins, agreed to buy out the Company over a period of years. After 1640, these 58 men – and their heirs – acquired unique privileges regarding land acquisition in the Plymouth Colony.

In 1627, the cattle, “which were the Companies,” were “equally divided to all the persons of the same company…” that included Hopkins and his wife.

Hopkins served as an assistant Governor of Plymouth from 1624 to 1636 and was a respected member of the Pilgrims despite the fact that he did not conform to the strict religious views of the more pious Separatists. The “7 March 1633” list of Plymouth Colony freemen shows Stephen Hopkins near the head of the list.

In 1630, the Puritans, a religious group that differed from Plymouth’s Separatist Pilgrims, came on 11 ships with John Winthrop to settle in Boston and the surrounding area and found the Massachusetts Bay Colony. The principal difference between the groups was that the Separatists were intent on religious independence from the Anglican Church, while the Puritans wanted its radical reform.

Sandwich was the first town settled on Cape Cod, but not by the Pilgrims. 7 men from Saugus village near Boston, including Puritans, founded it, and in 1638, Stephen Hopkins was granted permission by the Plymouth Colony Court to “erect a house at Mattacheese” and to “cut hay to winter.” Later called Yarmouth, this was the first Pilgrim house on the Cape and Hopkins’ house was the first to be built by an Englishman east of Sandwich. Stephen’s son, Giles, moved into this house to raise and care for his father’s cattle. His father never lived on the Cape.

The permanent, authorized settlement of Yarmouth started the next year, in 1639. Of its 22 settlers, only 6 were Pilgrims, including Giles.

In 1639, Stephen Hopkins’ wife died in Plymouth. He appears in 1641 as one of the “contributors” to a ship being built in the colony and again in 1643 as a juror.

1643 was an important year in Massachusetts. The Plymouth Colony joined with the Massachusetts Bay Colony (the Puritans), Connecticut and New Haven to form the “United Colonies of New England.”

Stephen Hopkins died at Plymouth between 6 June 1644, when his will was made, and 17 July 1644, when the inventory of his estate was taken. In his will he asked to be buried near his wife, and named his surviving children. The inventory included “diverse books” valued at 12s.

Long-time Governor William Bradford wrote in 1650: “And seeing it hath pleased Him to give me [William Bradford] to see thirty years completed since these beginnings, and that the great works of His providence are to be observed, I have thought it not unworthy my pains to take a view of the decreasings and increasings of these persons and such changes as hath passed over them and theirs in this thirty years…

“Mr Hopkins and his wife are now both dead, but they lived above twenty years in this place and had one son and four daughters born here. Their son became a seaman and died at Barbadoes, one daughter died here and two are married; one of them hath two children, and one is yet to marry. So their increase which still survive are five. But his son Giles is married and hath four children…His daughter Constanta is also married and hath twelve children, all of them living and one of them married.”

Kenneth Whittemore, Jr., retired as a Commander from the U.S. Navy, where he served with the Nurse Corps. He is Governor of the General Society of Mayflower Descendants in California, and on the board of the General Society of Mayflower Descendants, headquartered in Plymouth, MA.

Bev Nickerson was Governor of the San Diego Mayflower Colony and state Society newsletter editor.

Governor Gotlieb presented both speakers with copies of The Jamestown Century to commemorate their visit with First California Company.

Governor Gotlieb presented both speakers with copies of The Jamestown Century to commemorate their visit with First California Company.