First California Company is encouraging our members to give presentations about their ancestors at our meetings. Jim McCall and Martha Pace Gresham, both descendants of Ancient Planters Richard and Isabella Pace, gave the first of these at our annual meeting on June 18. This is a two-part synopsis.

Part One: Seeking Early Opportunity in Jamestown

By James H. McCall

Note: It is difficult to document the Paces at Jamestown. Most of its early colonial records were lost in the fiery destruction of Richmond in 1865. However, we are indebted for what we do know about them to researcher Martha McCartney for combing local land records and resources, archeologist Nick Luccketti for locating and showing us where they lived and my son for his own research and pictures of St. Dunstan and All Saints, Stepney, where they were married. We also used the sources and references listed below; many of the digital sources can be read by clicking on the hyperlinks in the text. You can also see more detail in the maps and illustrations by clicking on them. We also interpreted conjectures in several Pace-related genealogical books and web sites for our own suppositions.

The attraction of Jamestown was opportunity. Among the earliest families to settle was that of Richard and Isabella Pace and their young son, George. Both were investors in the Virginia Company of London and among the recipients of the first headrights or land grants. They exemplified the middle class English entrepreneurial immigrants who sought economic opportunity and were the backbone of Jamestown’s establishment. The Paces also played a key role in Jamestown’s survival.

Ordinary life in England was very difficult in the late 16th and most of the 17th centuries. The English economy was depressed and the population doubled from 2.3 to 4.8 million between 1520 and 1630; London grew from 90,000 to almost 200,000. Desperate societal conditions drove some in the middle class to seek relief from economic deprivations, urban distress and religious turmoil – the motivations for taking the extraordinary risks in colonizing Virginia.

|

| London in Richard Pace’s time |

The London suburbs east of the Tower of London is where we first find Richard Pace. He was probably born between 1580 and 1583 and lived in Wapping, or Wapping Wall, a major port and ship construction area. He was a carpenter and may have done well enough (and had the connections) to afford investing in the Virginia Company of London. One source suggests that his wife, Isabella Smythe Pace, may have been born in Westminster between 1587 and 1589. Her father may possibly have had some means, as she later demonstrated financial acumen and knew the values of money and property. They were married on October 5, 1608 at the ancient church of St. Dunstan’s, Stepney (now St. Dunstan and All Saints.)

|

| St. Dunstan and All Saints |

Both of the Paces were investors in Virginia Company of London. It was highly unusual for a woman like Isabella to have been an investor in her own right, and it could indicate that she had business aptitude and connections. We’re also uncertain when their son George was born.

Richard’s carpenter’s skills were needed in Virginia and the family came before 1616. One source suggests that their relationships with fellow colonists William Perry and William Powell may have brought all of them together in 1611. Jamestown’s 1612 population was 300, equivalent to the population of less than one of our suburban blocks today.

The Pace family lived under the “Lawes Divine, Morall and Martiall, etc.” until 1618, when the Virginia Company drafted a new legal code based on English common law to replace “the semi-military dictatorship” that had been in place since 1610. In 1616, the Virginia Company of London made land grants fifty acres to each of its investors (including both Paces) in lieu of a dividend that it was unable to pay from profits. A year later, to spur colonial immigration and agriculture, they began granting another fifty acres to Ancient Planters, those settlers – such as both Paces – who had arrived before 1616, paid their own passage and remained for three years. These were the New World’s first land patents owned by common citizens, instead of by the monarchy, aristocracy or Church, as had been the time immemorial practice in Europe and England. The colonists and investors then began trading and selling their properties, as land was the only form of savings and there were no colonial banks.

|

| Young women arriving in Jamestown |

Few other women were in Jamestown until 1619-20, when the Company began sending the first groups of marriageable women to help stabilize and establish the colony. The Paces reportedly invested in ships and the immigration of women in 1619-21.

The Paces likely initially lived at Jamestown. Records indicate that Richard Pace had, for a time, served as the overseer of Captain William Powell’s plantation on the lower side of the James River, but had left that post in order to seat his own land. Virginia land records also reveal that Pace also had a financial interest in a plantation that Captain William Powell intended to establish on the Chickahominy River.

|

| James River at Jamestown; Chickahominy at upper left |

Jamestown’s population had grown to 900 by 1620. Richard and Isabella finally had their grants confirmed on December 5, 1620. Isabella received hers in an era when women did not usually own land. The explanation may be found in one of the petitions of the First Assembly in 1619, where “It is prayed that it be plainly expressed” that there be shares for wives “because that in a new plantation it is not known whether man or woman be the most necessary.” Richard also took advantage of the new “headright” system, and was granted 50 acres for each of six persons he brought over in August 1621, giving him an extra 300 acres.

|

| Location of Pace’s Paines in Surry |

Richard and several of his friends formed Pace’s Paines as a sub-colony, which was situated across the river from Jamestown on a high bluff above the colony’s unhealthy swamps. “Paines” is thought to be an old English term for acres or fields. Richard Pace was the Commander and William Perry was the military Captain. As his and Isabella’s holdings consisted of 600 acres, he was considered the largest landholder and his name was used to identify the group.

Nick Luccketti, formerly a Jamestown Rediscovery archeologist and now a principal in the James River Institute of Archeology, discovered main site of Paces Paines on what is now the 300-acre Mt. Pleasant Plantation, still directly across the river from Jamestown.

|

| Pace’s Paines was located in the field to the right center |

Pace’s Paines was probably a palisaded settlement with one-story buildings of split logs made into clapboards. The early settlers used this method; clapboard was one of the first commodities sent back to England by the planters. The settlement’s lands were cleared and planted in tobacco.

Over 15,000 Indians are estimated to have been living around Jamestown about 1607, which was likely about the same in 1622.

|

| Powhatan settlements in 1607 |

The 1622 Population in the English settlements was estimated at 1,300.

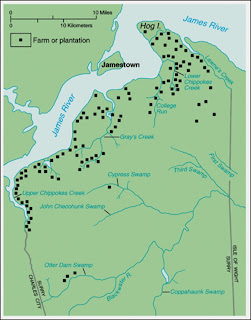

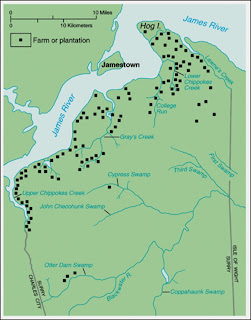

|

English settlements in 1622;

Pace’s Paines is opposite Jamestown, to the left

of where Gray’s creek empties into the James. |

On March 22, 1621/22, Powhatans and their allies mounted a well-planned and coordinated surprise attack throughout the colony to drive the English from their ancestral homelands. This shattered the tenuous eight-year peace from the Rolfe/Pocahontas marriage. Contrary to a perpetuated myth, it was not Good Friday, which fell on April 19 that year.

Early that morning, an Indian boy, Chanco, William Perry’s servant, was living in the Pace household. He warned Pace of the impending attack, and the family and Chanco very likely went to the beach where Gray’s Creek empties into the James and rowed a small boat over two miles to Jamestown to warn its residents.

|

| Plaque memorializing Chanco at Jamestown church |

Over a score of outlying plantations were decimated, but Chanco’s warnings helped to spare Jamestown itself. Over a quarter of the settlers were killed, of whom many were mutilated. It is likely that more lost their lives and others (mainly women) were taken captive. Almost all the settlements’ farm animals were also killed.

|

| Contemporary depiction of 1622 attack |

Following the attack, a census called “List of the Living” was taken, dated Feb. 16, 1623. While Richard and Isabella were not listed, there is an entry reading: “Richard Pearse and uxer (wife)” who were then living “at the Neck of Land” near Jamestown, so it is possible that this Richard Pearse was Richard Pace. Also, Richard’s friend, Thomas Gates was living there with his family. Richard and Isabella’s son, George, was also omitted from the “List of the Living.” He would have been about 13 years old at the time.

The Pace family was also not found in 1624 muster. Pace apparently died sometime after January 1623 but before February 16, 1624 He would have been in his early forties and Isabella and George survived him. By February 16, 1624, the widowed Isabella Smyth Pace had married his good friend and neighbor, ancient planter William Perry, and once again was living in Jamestown. Afterwards, a record of May 9, 1625, shows that Isabella, now known as Mistress Perry, testified at a witchcraft trial. Captain William Perry died in 1637 and there is no further record of Isabella after that, but some speculation that she married again before she is believed to have died before 1645, when she would have been in her mid to late fifties.

George Pace is absent from the records until September 1628, when he received the patent for 400 acres at Pace’s Paines as his father’s primary heir, which was adjacent to his mother’s land that she acquired as an Ancient Planter and more that she had bought. By 1635, they had apparently traded or sold Pace’s Paines to William Swann and, with his stepfather, moved to Charles City. George later went on to become a successful planter.

Jamestown’s population in 1625 was about 1,300. The effect of the Indian assault on the colony was not unlike that of terrorists’ plane crashes into the World Trade Center and Pentagon almost four centuries later. The news of this catastrophe was one of the final blows for its private backers. New settlers who had arrived from London in spring 1623 introduced a virulent epidemic that killed more colonists than the Powhatan raids, which also helped to precipitate the Company’s demise.

There was a realization that less than one of six had survived of about 7,000 of those who had emigrated to establish Virginia. A royal inquiry led to the revocation of the Company’s charter and its dissolution in 1624. The Company’s investors (including the Paces) were wiped out with a loss estimated at over £200,000 (as valued at the time, or the 2010 equivalent of over $46,000,000.)

Part Two: On From Jamestown

By Martha Pace Gresham

We must talk of Isabella Smyth Pace. She and Richard were investors in the Virginia Company and therefore may have been financially better off that most. She appears to have been an intelligent, tough-mined woman who evidently understood business. Isabella saw the bigger picture and was able to take advantage of the opportunities offered in their rugged new world. Remember that our ancestors were not accustomed to the high standard of living that we enjoy today. There were no super-markets and food was always scarce, no drugstores, clothes were made at home, usually from cloth woven at home.

Isabella had received her own head-right land of 100 acres and claimed it in Surry County next to Richard’s acreage. She also received, at one time, 300 acres on Jamestown Island, which she had to cultivate or lose. Some sources indicate that she acquired some of her land by head rights from her investment in the ships that brought women of high character to the colony as prospective wives.

Isabella was widowed in her mid-thirties and quickly remarried her husband’s good friend and neighbor, William Perry. Their remarriage was necessary, as in all frontier communities, for the shelter and protection of the women and children. With this marriage, she still maintained as separate property the Richard Pace family’s holdings for her son, George, until he reached his maturity. (This was unusual at that time as the wife’s property always went to the husband.)

The Perrys also had a son, Henry, so George Pace had a half-brother. Later, after William Perry died, Isabella married George Menifie, who was the wealthiest man in the colony. He was an attorney who trafficked in land, tobacco and laborers and also a member of the Council. Isabella’s second son, Henry Perry, eventually married George Menife’s daughter and also was a member of the Council.

Isabella and her son George made several land trades in Surry County and they eventually traded that property away. George married Sara Maycock, the only heir of the minister, Samuel Maycock who was killed in the March 1622 Indian uprising.

With the marriage came 1,700 acres that Sara had inherited from her father. George and Sara continued to live in Virginia, reared 4 children, Richard II, John, Elizabeth and Thomas. Richard II married Mary Knowles in 1661 and had 8 children. Jim McCall and I are both descended from this couple; Jim from their youngest son Richard III, who married Rebecca Poythress, and I am descended from an older son John, who married Elizabeth Lowe.

Housing was minimal, even for those who were wealthy enough to invest in the Virginia Company. At first, the immigrants lived in small huts at the Fort, and then built houses with one room where the family lived, ate and slept. If a second room was added it was usually a kitchen, but more often these additional rooms were separate structures, such as a kitchen away from the house in case of fire, separate places for indentured servants, store rooms, barns, weaving rooms, chicken houses, etc. Thus, a homestead was often referred to as “a village.”

Once the settlers started raising tobacco, their homes were temporary shelters for the family, and not expected to last more than 4 to 7 years. Every few years the tobacco land would wear out; the house would be torn down, the wood burnt – it was free and plentiful – and the nails carefully saved. The families moved on up the river to new land. England did not allow industry in its colonies and nails had to be imported; they were thus expensive. Also, since tobacco was king, if there were any carpenters in the colony, they were not building houses for others; they were planting tobacco for themselves.

|

| The framing of an early seventieth century story-and-a-half single bay house and a similar dwelling (inset). Conjectural drawing by H. Warren Billings. |

The house shown in the picture has a fireplace but many houses were built English style with a fire in the middle of the floor and the smoke escaping through a vent under the eaves.

As life got easier, the population increased with the constant influx of new settlers and available land was being filled. By 1700, tobacco was no longer king and there was an over supply. The number of poor increased, the younger Pace sons moved on, north into Pennsylvania, west into the Virginia hinterlands and south into North Carolina. The 4th generation Pace descendents had moved into North Carolina’s Bertie and Cowen Counties and a son, William, was in North Hampton Co. during the Revolution.

|

| 1751 map of Pennsylvania, Virginia, New Jersey and North Carolina; drawn by Joshua Fry and Peter Jefferson |

At this time the few main roads that were maintained ran North and South. They were initially only horse paths for the mail, i.e., the post road along the coast (which much of route Interstate 95 from Florida to Boston now follows). East-west roads, if any, were wagon trails. The western mountain ranges such as the Blue Ridge and Appalachians were also formidable barriers.

There is a line of waterfalls on every river that flows into the Atlantic Ocean along the east coast of the United States. This line extends for 900 miles from Pennsylvania to Georgia and marks the end of navigation upstream. The Fall Line also divides the area into two separate geological entities.

Farmers to the west of these falls found it impossible to easily get their produce to market via boat. (After the American Revolution, industry was located on the Fall Line to take advantage of the waterpower.) Between 1735 and 1750, a Fall Line Road was built from Fredericksburg, Virginia to Augusta, Georgia.

As the Paces and others pushed further inland, this Fall Line necessitated a new approach to farming. Brothers William and James Pace established numerous farms in North Carolina and continued to actively acquire and trade land. They raised wheat and oats for livestock, cattle and horses. It was too costly to move tobacco west beyond the Fall Line, but they could drive cattle and horses to market on their own four legs; thus, we had the early cattle drives out of the west.

|

| Daniel Boone’s Wilderness Trail |

At this time, the Transylvania Company owned The Transylvania Purchase in Tennessee and wanted to open it for settlement. Daniel Boone was hired in 1775 to blaze a trail across the mountains from Virginia into the Tennessee territory. Boone assembled 30 axmen to blaze the trail following the Great Warriors Path from the Holston Valley through Southwest Virginia then across the Cumberland Gap and into Tennessee. Thus, he opened his famous Wilderness Trail.

After the Revolution, as in all wars, there was a lot of relocation. In 1790, members of the next generation, William Pace and his wife, Ruth Lambert, moved to Clarke County, Georgia, which was the fourth state to ratify the Constitution in 1788. There must have been something special about Georgia because Jim McCall’s branch of the family later also moved to the Carolinas and Georgia during the same period.

William and Ruth’s family consisted of 8 sons and 2 daughters. Two or three of the older sons moved on to Tennessee, which had become a state in June 1796. After a few years, these sons returned to Georgia to encourage the rest of the family to join them. The father and a number of the children returned to Tennessee. Nothing is mentioned in the records about the mother, Ruth Lambert, so we can assume that she had died. In fact she so rarely appeared in the records that it greatly frustrated later family genealogists. Eventually all of William’s children settled in Tennessee.

Moves like this were not easy. They took a lot of planning and good timing. Families would move with all their household possessions, necessities for the trip and supplies to see them through the winter in case they arrived too late for the planting season. Extended families and friends or neighbors would move together for strength and safety. Often there were 60 or 70 pack-horses plus cattle and goats, dogs, chickens, etc., in the train.

By the War of 1812, my ancestors in this Pace line had settled in Rutherford County, Tennessee and were friends and neighbors of Andrew and Rachael Jackson. In September 1813, the Spanish in Florida were stirring up Indian Tribes in southern Georgia against the United States. Andrew Jackson was ordered to lead the American forces into the area and settle the trouble. Jackson called for the Tennessee Mounted Riflemen to back him in battles along the Mississippi/Georgia Border in this the Creek or Red Stick War. William’s sons, James and John answered the call along with a young man from Eastern Tennessee named Davy Crockett. They fought the battles, returned home and planted their crops thinking that their war was over.

President Monroe, however, ordered Jackson onto New Orleans, Louisiana. Monroe had learned of a huge buildup of British troops in the Caribbean. Jackson again called for the Tennessee Mounted Riflemen to go Louisiana along with the Kentucky Long Rifles, the Creoles who had escaped from the slave uprising in Haiti, the French in New Orleans, freed men of color and even pirates. Five PACE brothers answered this call. James Pace was made captain. Jackson was uneasy with the idea that the British would attach New Orleans. He believed that their strategy was to invade at Mobile, Alabama.

However, British Major-General Sir Edward Pakenham (brother-in-law Lord Nelson) had been promised the Governorship of all of Louisiana when the English defeated the Americans, and ordered that the English would attack New Orleans with 8,000 experienced British soldiers who recently had been transported from Waterloo, Belgium, where they had defeated Napoleon. Major General Pakenham was sure that he could easily defeat the rag-tag American Army in the Battle of New Orleans.

There are two things to remember about this battle:

- The War was over. The treaty of Ghent had been signed, but not ratified.

- It went on for about 6 weeks with small skirmishes and large battles.

For many years, French residents had plantations, the Chalmette group, about seven miles south of New Orleans. In December 1814, the British overran the plantation of Jacques Villere, and the Americans attacked on the night on December 23rd to drive them out in the “Night Battle of New Orleans.” It was a vicious battle with 213 American casualties and a larger number of English.

|

| Chalmette Battle Field Cemetery |

Captain James Pace was killed in this battle on December 23, 1814 and we believe that he is buried in the Chalmette Battlefield Cemetery. This battle was followed two weeks later by the victory at New Orleans on January 8, 1815.

This was a great triumph. Andrew Jackson picked a choice spot to throw up his tall defense barricade. The Mississippi river was on the west and a dangerous swamp on the east of the battlefield. The British had to advance down a narrow corridor, for they were scared to death of the swamp. Only 28 Americans were killed in this battle and the British lost 3,200 men that day, including Major General Pakenham. For the Pace family, there was a second tragedy, as John Pace was also killed. This date, January 8th, was celebrated as a National Holiday until the Civil War.

Mary Ann Loving Pace, Captain James Pace’s widow, had to struggle to collect her husband’s back army pay. She was required to put up a $1,000.00 bond, which was probably the Plantation. Imagine how much a $1,000 represented in 1815 on the frontier where there was very little money in circulation.

In the early 1830s, two sons of Captain James and Mary Ann Loving Pace, William Franklin and James, were converted to the Mormon faith by John D. Lee. They sold their plantations, manumitted their slaves except for the few that chose to stay with the family and moved to the Mormon Settlement in Nauvoo, Ill. At that time, Nauvoo was the largest settlement in Illinois with about 12,000 people (Chicago was somewhat smaller.) The Pace brothers had their large farms across the Mississippi River in Southwestern Iowa.

Their neighbors were fearful of their potential political power and distrustful of this new religion. As a result, on June 27, 1844 the Mormon leader Joseph Smith and his brother were martyred. In February 1846 the Paces, along with the other converts, were driven out of Nauvoo by mobs and they moved west across Iowa with the church leader, Brigham Young. That year the weather had been extremely cold and the Mississippi River was frozen solid. The Mormons were thus able to escape by driving their wagons on the ice across the river from Illinois to Iowa.

The map below shows the areas of the Western United States claimed by various countries in 1840. The future state of Utah was part of Mexico. When they first arrived in the Salt Lake area, the early Mormon leaders had no idea to whom they owed allegiance. The area on the map claimed by Mexico was the territory gained by the United States with their victory in the Mexican War and the subsequent Gadsden Purchase.

James Pace was one of the 500 Mormon men who volunteered to join the Mormon Battalion as part of the United States Army of the West; these men were to fight in the War with Mexico. The United States officers who headed the Mormon Battalion appointed James Pace (Uncle Jimmy) a Lieutenant and, therefore, as an officer he was a gentlemen and had to have servants. He thus took as servants his 15 year old son William Bryant Pace and his 15 year old nephew Wilson Daniel Pace, my great-grandfather. These boys were cook’s helpers and I imagine got in on a lot of jobs on the long trek west.

The Mormon Battalion was a part of Kearney’s Army of the West. It was a very unusual military group in that most of the men could read and write at a time when only about

1½ % of the United States’ population was literate. We now know of at least 10 diaries that were written by members recording the march. Many men were highly trained artisans, carpenters, furniture-builders etc.

They arrived in San Diego on January 29, 1847 after a march of 1,900 miles. Here they raised the American Flag, cleaned up the deserted Mexican Fort on the hill above Old Town; built brick kilns and fired the first bricks in San Diego. They then dig 18 wells lined them with bricks and built the first San Diego Courthouse…out of bricks of course.

|

| Early San Diego, California. Several of these buildings are in use today |

The Battalion rested several months at the Mission San Luis Rey in Oceanside where one of their guides, Jean Carbonneau (the son of Sacajawea) was made Alcalde. Then they were called to Los Angeles where they celebrated, with Kearney’s battalion of Army of the West, the first July 4th in California in 1847 at Fort Moore. The army had harvested two tall trees from the San Bernardino mountains, spliced them together and set up a flagpole. However, they forgot to rig the pole for the flag and my great grandfather, Wilson Daniel Pace, (that 15 year old boy) climbed the pole and nailed the flag on it. The celebration then could go forward with military parades, the reading of the Preamble of the Constitution in English and Spanish, the singing of Yankee Doodle, etc.

Their enlistment ended in Los Angeles on July 16, 1847 and the men made their way back to Utah and Iowa for their families. Eventually this line of Paces settled and thrived in Utah and Arizona.

The Paces had made it from sea to shining sea and here is a message for some present-day descendents of Richard and Isabella.

Sources and References

Billings, Warren M.:

Editor: The Old Dominion in the Seventeenth Century; A Documentary History of Virginia, 1606-1700, Revised Edition; (Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press, for the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture at Williamsburg, 2007.)

Billings, Warren M., John E. Selby, and Thad W. Tate:

Colonial Virginia: a History. (White Plains, NY: KTO, 1986).

Howard, Bruce A.:

A Sketch and History of Our Colonial Ancestors from 1619 to 1799; (Quitman, MS, Specialty Printing and Publishing, 1998).

Kupperman, Karen Ordahl:

The Jamestown Project; (Cambridge MA, Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2007.)

Langguth, E. J.: Union 1812 (New York, Simon and Schuster, 2007)

London Metropolitan Archives

40 Northampton Road

London EC1R OHB

McCartney, Martha W.:

Virginia Immigrants and Adventurers, 1607-1635: A Biographical Dictionary; (Baltimore, Genealogical Publishing Company. 2007)

Pace, James:

The Autobiography and Diary of James Pace 1811-1888, (Brigham Young University Library; 1946. Distributed by the Pace Society of America)

Stanard, Mary Newton:

A History of the Jamestown Period 1607-1700; 400th Anniversary edition (Philadelphia and London, J. P Lipcott Co.; 1928 (reprinted 2007)

Turner, Freda Reid (ed.):

The Pace Family 1607-1750, (Roswell, New Mexico, W.H. Wolfe Associates, Distributed by the Pace Society of America; 1993.)

Digital Sources

Brown, Kathleen M.:

Fausz, J. Frederick:

Officer, Lawrence H.: